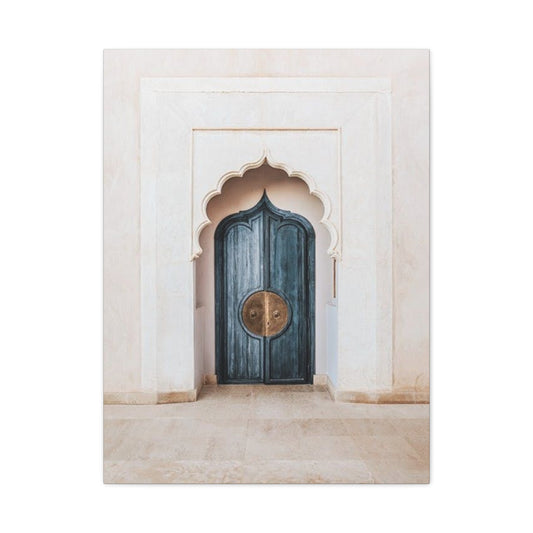

Collection: Moroccan Wall Art

The Ultimate Guide to Moroccan Wall Art: Transforming Spaces with Timeless Beauty

The mesmerizing realm of Moroccan decorative arts emerged from a confluence of civilizations spanning over thirteen centuries, creating an unparalleled artistic legacy that continues to captivate contemporary interior design enthusiasts worldwide. The foundational elements of this extraordinary craft tradition can be traced back to the Berber civilizations that inhabited the Atlas Mountains and coastal regions long before the Arab conquest of North Africa in the 7th century.

During these formative periods, indigenous artisans developed sophisticated geometric vocabularies that would later become the cornerstone of Islamic artistic expression throughout the Maghreb region. The Berber communities possessed an innate understanding of mathematical proportions and spatial relationships, evidenced in their intricate textile patterns, pottery designs, and architectural embellishments. These early practitioners established fundamental design principles that emphasized symmetry, repetition, and infinite extension - concepts that would profoundly influence subsequent artistic movements.

The arrival of Arab traders and conquerors brought revolutionary changes to the existing artistic landscape, introducing new materials, techniques, and philosophical approaches to decoration. The Islamic prohibition against figurative representation in religious contexts paradoxically liberated artists to explore abstract and geometric forms with unprecedented creativity and sophistication. This constraint became a catalyst for innovation, pushing craftspeople to develop increasingly complex pattern systems that could convey spiritual meaning through pure mathematical beauty.

The Ancient Origins of North African Decorative Practices

Byzantine and Persian influences filtered into the region through trade routes and diplomatic exchanges, contributing sophisticated color palettes and refinement techniques that elevated local craftsmanship to extraordinary heights. The synthesis of these diverse cultural streams created a unique artistic vocabulary that was distinctly Moroccan while remaining connected to broader Islamic aesthetic traditions. This cultural fusion established the foundational framework for what would become one of the world's most recognizable decorative art forms.

The Almoravid and Almohad dynasties of the 11th and 12th centuries marked pivotal moments in the evolution of Moroccan artistic expression. These powerful Berber dynasties commissioned grand architectural projects that showcased the highest levels of craftsmanship and artistic achievement. The construction of magnificent mosques, palaces, and madrasas provided platforms for master artisans to experiment with new techniques and push the boundaries of decorative possibility.

During this golden age, the distinctive characteristics that define authentic Moroccan decorative arts became firmly established. The emphasis on mathematical precision, the celebration of geometric complexity, and the masterful use of color emerged as defining features of the tradition. Artisans developed specialized tools and techniques that enabled them to achieve levels of precision and intricacy that remain impressive by contemporary standards.

The establishment of artisan guilds during the medieval period created structured systems for preserving and transmitting specialized knowledge across generations. These professional organizations maintained quality standards, protected trade secrets, and ensured the continuity of traditional methods. The guild system also facilitated innovation by creating environments where master craftspeople could collaborate and share expertise across different specialties.

The Marinid dynasty of the 13th and 14th centuries ushered in what many consider the classical period of Moroccan decorative arts. This era witnessed the construction of architectural masterpieces that continue to serve as inspiration for contemporary artists and designers. The Bou Inania Madrasa in Fez and the Alhambra in Granada represent pinnacles of artistic achievement that demonstrate the sophisticated mathematical understanding and aesthetic sensibilities of medieval Moroccan craftspeople.

Spiritual Symbolism and Sacred Geometry in Islamic Ornamentation

The profound spiritual dimensions of Moroccan decorative traditions extend far beyond mere aesthetic considerations, reflecting deep philosophical and theological concepts that have shaped Islamic culture for over a millennium. The geometric patterns that characterize authentic Moroccan designs serve as visual representations of cosmic order and divine unity, creating meditative environments that facilitate contemplation and spiritual reflection.

The concept of tawhid, or divine unity, finds expression through the infinite repetition and extension of geometric patterns. These designs symbolically represent the boundless nature of divine creation while simultaneously demonstrating the underlying mathematical principles that govern natural phenomena. The seamless integration of individual elements into larger compositional schemes mirrors Islamic theological concepts regarding the relationship between individual souls and universal consciousness.

The eight-pointed star, known as the khatam or seal of the prophets, occupies a central position in the symbolic vocabulary of Islamic decoration. This fundamental form generates countless variations and combinations, serving as the basis for some of the most sophisticated pattern systems ever developed. The star's eight points traditionally represent the eight beatitudes mentioned in Islamic scripture, while its radiating geometry suggests the emanation of divine light throughout creation.

Sacred proportions based on mathematical relationships found in nature permeate authentic Moroccan decorative schemes. The golden ratio, various root rectangles, and polygonal constructions create harmonious relationships between different design elements that resonate with viewers on both conscious and subconscious levels. These proportional systems were not merely aesthetic choices but reflected deeply held beliefs about the mathematical structure underlying all creation.

The interweaving patterns characteristic of Moroccan geometric compositions symbolize the interconnectedness of all existence while demonstrating the unity that underlies apparent diversity. These interlacing designs create visual metaphors for the complex relationships between individual elements and their participation in larger cosmic patterns. The continuous flow of lines and forms suggests the eternal nature of divine presence throughout the material world.

Color symbolism plays an equally important role in the spiritual dimensions of Moroccan decorative arts. Traditional color palettes reflect not only aesthetic preferences but also symbolic associations with various spiritual states and cosmic principles. Blue represents the infinite sky and divine transcendence, green symbolizes paradise and spiritual renewal, while earth tones connect viewers to the material realm and natural cycles.

The absence of beginning or end in properly executed geometric patterns creates visual analogies for divine eternity and the cyclical nature of spiritual development. These endless designs invite contemplation and meditation, providing focal points for spiritual practice while simultaneously serving decorative functions. The mathematical precision required for their execution also reflects Islamic emphasis on order, harmony, and perfection as divine attributes.

The hierarchical organization of pattern elements within larger compositional schemes mirrors Islamic cosmological concepts regarding different levels of existence and spiritual attainment. Primary geometric forms give rise to secondary and tertiary patterns through systematic subdivision and elaboration, creating complex visual hierarchies that correspond to metaphysical understanding of reality's multilayered structure.

Evolution Through Dynastic Periods and Architectural Monuments

The remarkable evolution of Moroccan decorative traditions across successive dynastic periods reveals a continuous process of refinement and innovation that spans nearly eight centuries of artistic development. Each ruling dynasty contributed distinctive elements to the growing vocabulary of ornamental forms while maintaining essential connections to foundational principles established during earlier periods.

The Almoravid period of the 11th and early 12th centuries established many fundamental characteristics of Moroccan architectural decoration. The Kutubiyya Mosque in Marrakech exemplifies the austere elegance that characterized Almoravid aesthetic preferences, featuring geometric patterns executed with mathematical precision and subtle color variations that create sophisticated visual effects through purely abstract means.

The subsequent Almohad dynasty expanded upon Almoravid foundations while introducing new elements of grandeur and complexity. The Giralda Tower in Seville and the Hassan Tower in Rabat demonstrate Almohad mastery of monumental scale and proportional harmony. These structures showcase the evolution of geometric pattern systems toward increased sophistication and the development of new constructional techniques that enabled more ambitious decorative schemes.

The Marinid period of the 13th and 14th centuries represents the classical flowering of Moroccan decorative arts. During this era, artisans achieved unprecedented levels of technical mastery and artistic sophistication. The Bou Inania Madrasa in Fez and Meknes showcase the full maturation of traditional techniques, featuring incredibly complex geometric compositions executed with flawless precision in multiple media including carved stone, sculpted plaster, painted wood, and mosaic tilework.

The Nasrid dynasty's creation of the Alhambra in Granada during the same period established new standards for palatial decoration that influenced subsequent developments throughout the Islamic world. The extraordinary geometric compositions adorning the Court of the Lions and the Hall of the Abencerrages demonstrate the ultimate refinement of mathematical pattern systems and their integration with architectural space.

The Saadian renaissance of the 16th and early 17th centuries witnessed a remarkable revival of classical traditions combined with innovative approaches to color and composition. The Saadian Tombs in Marrakech and the El Badi Palace showcased new interpretations of traditional forms while maintaining essential connections to earlier periods. This era also saw increased exchange with other Islamic regions, particularly the Ottoman Empire, leading to subtle influences that enriched local traditions.

The Alaouite dynasty, which continues to rule Morocco today, has overseen both the preservation of traditional crafts and their adaptation to contemporary circumstances. The construction of the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca during the late 20th century demonstrated the continued vitality of traditional techniques while showcasing their application on an unprecedented scale using modern construction methods.

Throughout these dynastic transitions, master craftspeople maintained guild systems that preserved essential knowledge while allowing for gradual innovation and adaptation. The transmission of specialized techniques across generations ensured continuity of quality and authenticity while providing frameworks for creative development within established parameters.

The architectural monuments created during these various periods continue to serve as primary sources and inspiration for contemporary artisans and designers. These historic examples provide authentic models for traditional techniques while demonstrating the potential for creative interpretation within established frameworks. The careful study of these masterpieces remains essential for understanding the full depth and complexity of Moroccan decorative traditions.

Traditional Craftsmanship Methods and Guild Systems

The extraordinary quality and consistency that characterize authentic Moroccan decorative arts result from sophisticated guild systems and traditional training methods that have preserved specialized knowledge for over seven centuries. These professional organizations created structured frameworks for learning, practicing, and transmitting complex skills while maintaining quality standards that ensure the integrity of traditional techniques.

The master-apprentice relationship forms the cornerstone of traditional craft education, requiring years of dedicated study and practice under expert guidance. Apprentices typically begin their training in early adolescence, spending initial years learning fundamental techniques and developing the manual dexterity required for precise work. This extended preparation period ensures that practitioners acquire not only technical skills but also deep understanding of traditional principles and aesthetic values.

The progression from apprentice to journeyman to master craftsperson follows carefully structured stages that test both technical competence and creative ability. Journeymen must demonstrate mastery of traditional techniques while developing personal styles within established parameters. The achievement of master status requires the ability to design original compositions, supervise other craftspeople, and maintain the highest quality standards under various working conditions.

Specialized tools developed specifically for different aspects of Moroccan decorative work represent centuries of accumulated practical knowledge. The menqach tools used for cutting geometric patterns in zellige tiles, the compass systems employed for laying out complex geometric compositions, and the various brushes and pigment preparation methods used in painted decoration all reflect sophisticated understanding of materials and processes.

The guild system also established quality control mechanisms that ensured consistency and authenticity across different workshops and regions. Master craftspeople served as quality inspectors, examining finished work and certifying that it met established standards. This system maintained the reputation of Moroccan decorative arts while protecting consumers from inferior products and preserving the economic viability of traditional crafts.

Knowledge preservation within guild systems relied heavily on oral tradition and hands-on demonstration rather than written documentation. Master craftspeople possessed extensive memorized repertoires of pattern systems, proportional relationships, and technical procedures that were passed directly to apprentices through intensive personal instruction. This transmission method ensured that tacit knowledge and subtle refinements were preserved along with explicit technical information.

The seasonal rhythms of traditional craft production reflected both practical considerations and cultural values. Many decorative processes required specific environmental conditions or seasonal materials, creating annual cycles that coordinated different aspects of production. These rhythms also provided opportunities for rest, reflection, and community celebration that strengthened social bonds within artisan communities.

Regional specializations developed within the broader framework of Moroccan decorative traditions, with different cities and areas becoming renowned for particular techniques or materials. Fez became the center for fine geometric tilework, Tetouan specialized in painted wooden decoration, while Marrakech developed distinctive approaches to carved plaster and stone work. These regional variations enriched the overall tradition while maintaining essential unity of principles and methods.

Regional Variations and Distinctive Local Traditions

The rich diversity of Moroccan decorative traditions reflects the influence of distinct regional cultures, local materials, and historical circumstances that shaped artistic development across different areas of the country. These regional variations demonstrate how universal principles of Islamic geometric art adapted to specific environmental conditions and cultural preferences while maintaining essential unity of purpose and method.

The imperial city of Fez established itself as the premier center for sophisticated geometric decoration, particularly in the medium of zellige mosaic tilework. The clay deposits around Fez provide ideal material for creating the fine-grained tiles that characterize authentic zellige work, while the city's long history as a center of learning and culture created an environment that supported the highest levels of artistic achievement. Fassi artisans developed distinctive approaches to color combination and geometric complexity that set standards emulated throughout the Islamic world.

The subtle variations in Fez geometric patterns reflect centuries of refinement and innovation within traditional frameworks. Local master craftspeople developed signature approaches to proportion, color distribution, and pattern density that created recognizable regional characteristics while maintaining connection to broader Islamic geometric principles. The distinctive deep blue glazes and complex star-and-polygon systems associated with Fez work represent unique contributions to the global vocabulary of Islamic decoration.

Marrakech developed its own distinctive traditions that reflected the city's position as a crossroads between sub-Saharan Africa and the Mediterranean world. The warmer climate and different clay deposits of the Marrakech region influenced both the technical aspects of production and the aesthetic preferences of local artisans. Marrakchi work tends toward earthier color palettes and slightly different proportional systems that create distinctive visual effects while maintaining connection to traditional principles.

The influence of trans-Saharan trade routes on Marrakech decorative traditions can be seen in certain motifs and color combinations that reflect contact with sub-Saharan African cultures. These subtle influences enriched local traditions without compromising their essential Islamic character, demonstrating the adaptability and absorptive capacity of traditional Moroccan decorative systems.

Tetouan and the northern regions of Morocco developed distinctive approaches to painted wooden decoration that reflected both Andalusian influences and local preferences. The close historical connections between Tetouan and Al-Andalus resulted in decorative traditions that preserved many elements of Spanish Islamic art while adapting to local conditions and materials. The intricate painted geometric patterns characteristic of Tetouan work display exceptional refinement and sophistication in both design and execution.

The coastal regions of Morocco developed their own variations that reflected maritime influences and trade connections with other Mediterranean cultures. These areas produced distinctive approaches to color and proportion that incorporated subtle influences from various trading partners while maintaining essential Moroccan characteristics. The integration of these foreign elements demonstrates the flexibility and adaptability of traditional Moroccan decorative principles.

Mountain regions developed simplified but no less sophisticated approaches to geometric decoration that reflected different lifestyle patterns and material availability. The Berber communities of the Atlas Mountains maintained distinctive traditions that influenced lowland urban practices while preserving ancient design principles that predate the Islamic conquest. These mountain traditions provide important links to the pre-Islamic foundations of Moroccan decorative arts.

Contemporary Preservation and Revival Movements

The remarkable vitality of contemporary Moroccan decorative arts reflects successful efforts to preserve traditional knowledge while adapting ancient techniques to modern circumstances and global markets. These preservation and revival movements have ensured the continuity of specialized skills while creating new opportunities for contemporary practitioners and expanding international appreciation for authentic Moroccan craftsmanship.

The Moroccan government has played a crucial role in supporting traditional crafts through various institutional initiatives and educational programs. The establishment of specialized training centers, the documentation of traditional techniques, and the certification of authentic products have helped maintain quality standards while providing economic opportunities for new generations of artisans. These efforts have been particularly important in urban areas where traditional guild systems faced challenges from modernization and changing economic conditions.

International recognition of Moroccan decorative arts as intangible cultural heritage has provided additional support for preservation efforts while raising global awareness of the sophistication and historical importance of these traditions. This recognition has facilitated cultural exchange programs, educational initiatives, and collaborative projects that benefit both traditional practitioners and international scholars and designers.

Contemporary master craftspeople have embraced new technologies and materials while maintaining essential connections to traditional principles and methods. The use of modern tools for pattern layout, improved kilns for tile firing, and better transportation systems for materials has enhanced productivity without compromising quality or authenticity. These technological adaptations demonstrate the flexibility of traditional systems and their capacity for evolution within established parameters.

The revival of interest in handmade decorative arts within Morocco itself has created new markets for traditional products while encouraging young people to consider careers in traditional crafts. This domestic revival has been particularly important for maintaining the social and cultural contexts that support authentic traditional practice. The integration of traditional decorative elements in contemporary Moroccan architecture has provided ongoing opportunities for skilled practitioners while demonstrating the continued relevance of ancient techniques.

International demand for authentic Moroccan decorative products has created export opportunities that support traditional communities while spreading appreciation for genuine craftsmanship worldwide. This global market has encouraged the development of new product lines and applications while maintaining emphasis on quality and authenticity. The success of these export initiatives demonstrates the universal appeal of traditional Moroccan aesthetic principles and the superior quality of authentic handcrafted products.

Contemporary designers and architects working in Morocco and internationally have found innovative ways to incorporate traditional decorative elements in modern contexts, creating exciting new applications for ancient techniques. These contemporary interpretations demonstrate the timeless appeal and versatility of traditional Moroccan decorative principles while providing new directions for creative development within established frameworks.

Educational programs in universities and design schools have begun incorporating the study of traditional Moroccan decorative arts into their curricula, ensuring that new generations of designers and architects understand and appreciate the sophistication of these ancient traditions. This educational integration helps preserve specialized knowledge while encouraging innovative applications and interpretations that can extend the tradition into the future.

Sacred Mathematics in Islamic Geometric Design

The extraordinary sophistication of Moroccan geometric patterns reflects profound mathematical understanding that developed through centuries of artistic practice and spiritual contemplation. These intricate designs demonstrate how abstract mathematical concepts can be transformed into visually compelling decorative schemes that serve both aesthetic and contemplative purposes within Islamic cultural contexts.

The fundamental principle underlying all authentic Islamic geometric patterns is the concept of tawhid, or divine unity, which finds expression through the systematic repetition and extension of basic geometric forms. This philosophical foundation requires that individual pattern elements participate in larger compositional schemes that theoretically extend infinitely in all directions, creating visual metaphors for the boundless nature of divine creation while demonstrating the underlying mathematical order that governs natural phenomena.

The construction of Islamic geometric patterns relies on classical Euclidean geometry and the mathematical properties of regular polygons, particularly squares, triangles, hexagons, octagons, and twelve-pointed forms. These primary shapes generate increasingly complex secondary and tertiary patterns through systematic subdivision, rotation, and combination according to precise mathematical rules that ensure perfect fit and infinite repeatability.

The circle serves as the fundamental generative form from which all other geometric elements derive, symbolizing divine perfection and the unity that underlies apparent diversity. From the circle, master craftspeople construct regular polygons using only compass and straightedge methods, following mathematical procedures that date back to classical Greek geometry but were refined and extended by Islamic scholars and artisans.

The golden ratio and other mathematical proportions found in nature appear frequently in authentic Islamic geometric patterns, creating harmonious relationships between different design elements that resonate with viewers on both conscious and subconscious levels. These proportional systems were not merely aesthetic choices but reflected deeply held beliefs about the mathematical structure underlying all creation and the correspondence between geometric harmony and spiritual truth.

Symmetry operations including translation, rotation, reflection, and glide reflection provide the mathematical framework for pattern development and ensure that compositions maintain perfect balance and harmony regardless of their complexity or scale. The systematic application of these operations creates pattern families that share common mathematical properties while displaying infinite variation in detail and arrangement.

The concept of crystallographic symmetry groups, though not explicitly understood by medieval artisans, governs the mathematical structure of Islamic geometric patterns and provides modern tools for analyzing their construction and properties. The seventeen plane symmetry groups account for all possible ways of repeating patterns in two dimensions, and Islamic designers explored most of these possibilities with remarkable thoroughness and creativity.

Tessellation principles ensure that geometric patterns can be extended infinitely without gaps or overlaps, creating seamless decorative surfaces that symbolize the continuity and perfection of divine creation. The mathematical challenge of achieving perfect tessellation while maintaining visual interest and complexity pushed Islamic designers to develop increasingly sophisticated pattern systems that represent pinnacles of geometric achievement.

The hierarchical organization of pattern elements within larger compositional schemes reflects mathematical concepts of scale invariance and self-similarity that anticipate modern fractal geometry. These hierarchies create visual effects of infinite depth and complexity while maintaining overall unity and coherence, demonstrating the mathematical principles that govern both artistic composition and natural phenomena.

Star and Polygon Pattern Systems

The star-and-polygon pattern systems that characterize the most sophisticated Islamic geometric designs represent one of humanity's greatest achievements in decorative mathematics. These complex compositions demonstrate how simple geometric forms can be combined according to precise mathematical rules to create patterns of extraordinary beauty and infinite variety.

The regular star polygon, formed by connecting alternate vertices of a regular polygon, serves as the fundamental building block for most Islamic geometric patterns. Eight-pointed stars, twelve-pointed stars, and sixteen-pointed stars appear most frequently in Moroccan decorative traditions, though master craftspeople occasionally employed stars with other numbers of points to create special effects or accommodate specific architectural requirements.

The eight-pointed star, known as the khatam or seal of the prophets, occupies a central position in Islamic geometric vocabulary because of both its mathematical properties and symbolic significance. This fundamental form can be constructed from two overlapping squares rotated 45 degrees relative to each other, creating eight equal angles of 45 degrees that facilitate perfect tessellation with other geometric elements.

The systematic combination of different star forms with appropriate polygonal elements creates pattern families that share common mathematical properties while displaying remarkable visual variety. The relationship between stars and their surrounding polygons follows precise mathematical rules that ensure perfect fit and infinite repeatability, demonstrating the deep geometric understanding of Islamic pattern designers.

Secondary patterns emerge from the systematic subdivision of primary star-and-polygon compositions, creating increasingly complex hierarchical systems that maintain mathematical coherence while achieving extraordinary visual sophistication. These secondary patterns often display different symmetry properties from their parent compositions, adding layers of mathematical interest and visual complexity to the overall design scheme.

The mathematical principle of duality plays an important role in star-and-polygon systems, where patterns based on one type of fundamental element can be transformed into mathematically related patterns based on different elements. This duality creates families of related patterns that share common mathematical properties while displaying different visual characteristics, providing designers with systematic methods for creating variation within unified schemes.

Edge-to-edge and vertex-to-vertex relationships between pattern elements must satisfy strict mathematical requirements to achieve perfect tessellation. These constraints actually stimulate creativity by providing clear parameters within which designers must work, leading to the development of increasingly sophisticated solutions that demonstrate both mathematical ingenuity and aesthetic sensitivity.

The scaling properties of star-and-polygon systems allow patterns to be executed at any size while maintaining their mathematical coherence and visual impact. This scale invariance makes these patterns suitable for application to architectural elements ranging from small decorative details to large wall surfaces, providing unified decorative schemes that work effectively at multiple scales simultaneously.

Color distribution within star-and-polygon systems follows mathematical patterns that enhance the geometric structure while creating additional layers of visual complexity. The systematic alternation of colors according to geometric principles creates optical effects that emphasize certain aspects of the pattern while maintaining overall unity and balance.

Interlacing and Weave Patterns

The sophisticated interlacing patterns that appear throughout Moroccan decorative traditions represent another category of geometric achievement that demonstrates the mathematical ingenuity and aesthetic sensitivity of Islamic pattern designers. These complex weave systems create the visual impression of continuous bands or straps that pass over and under each other according to systematic rules, forming intricate knot-like compositions of extraordinary beauty and complexity.

The mathematical foundation for interlacing patterns lies in knot theory and topology, branches of mathematics that deal with the properties of continuous curves and their spatial relationships. Although medieval Islamic designers did not possess formal mathematical knowledge of these fields, their practical exploration of interlacing possibilities anticipated many important mathematical concepts by several centuries.

Basic interlacing patterns begin with simple geometric frameworks, typically based on square or triangular grids, within which continuous lines or bands are woven according to systematic over-and-under relationships. The mathematical challenge lies in creating patterns where all bands follow consistent weaving rules while maintaining visual balance and achieving perfect closure without loose ends or impossible intersections.

The development of complex interlacing patterns requires careful mathematical planning to ensure that all elements integrate properly and that the overall composition achieves the desired level of visual sophistication. Master pattern designers developed systematic methods for constructing these patterns that ensured mathematical correctness while providing flexibility for creative variation and adaptation to specific architectural requirements.

Multi-level interlacing systems create patterns where different sets of bands operate at different hierarchical levels, passing over and under each other according to complex but mathematically consistent rules. These multi-level systems achieve extraordinary visual depth and complexity while maintaining the clarity and readability that characterize the finest Islamic geometric compositions.

The mathematical concept of alternation plays a crucial role in interlacing patterns, where systematic changes in direction, color, or hierarchy create rhythmic variations that prevent visual monotony while maintaining overall coherence. These alternating systems demonstrate sophisticated understanding of mathematical periodicity and its application to decorative design.

Closed-loop interlacing patterns, where all bands form continuous circuits without beginning or end, create powerful symbols of eternity and divine perfection while demonstrating advanced mathematical understanding of topological properties. The construction of these closed-loop systems requires careful mathematical planning to ensure that all connections work properly and that the overall pattern achieves perfect symmetry and balance.

The integration of interlacing patterns with star-and-polygon systems creates hybrid compositions that combine the mathematical properties of both pattern types while achieving levels of visual complexity that exceed either system alone. These integrated patterns represent the highest achievements of Islamic geometric design and demonstrate the mathematical sophistication and aesthetic sensitivity of master pattern designers.

Color alternation within interlacing patterns follows mathematical rules that emphasize the three-dimensional illusion of bands passing over and under each other while maintaining overall visual unity. The systematic application of color according to geometric principles creates optical effects that enhance the pattern's spatial properties while contributing to its overall aesthetic impact.

Proportional Systems and Harmonic Relationships

The sophisticated proportional systems that govern authentic Moroccan geometric patterns reflect deep mathematical understanding and aesthetic sensitivity that developed through centuries of artistic practice and spiritual contemplation. These harmonic relationships create visual compositions that resonate with viewers on multiple levels while demonstrating the mathematical principles that underlie both artistic beauty and natural phenomena.

The golden ratio, approximately 1.618, appears frequently in Islamic geometric patterns through both explicit construction methods and emergent properties of complex compositions. This mathematical constant, which governs growth patterns in nature and has been recognized as aesthetically pleasing across cultures and historical periods, provides a foundation for proportional relationships that create visual harmony and balance.

Root rectangles based on the square roots of integers provide another category of proportional systems that appear throughout Islamic geometric design. The root-2 rectangle, root-3 rectangle, and root-5 rectangle each possess unique mathematical properties that generate distinctive visual effects when used as the basis for pattern construction, creating families of related compositions with shared harmonic properties.

The mathematical relationships between different regular polygons create natural proportional systems that Islamic designers exploited systematically in their pattern development. The fact that regular hexagons, squares, and equilateral triangles can tessellate the plane in specific combinations provides mathematical constraints that actually stimulate creativity by defining clear parameters for compositional development.

Modular proportional systems, where all dimensions relate to a basic unit measure through simple mathematical ratios, create coherent decorative schemes that maintain visual unity across different scales and applications. These modular systems facilitate the integration of patterns executed in different media while ensuring that all elements contribute to overall compositional harmony.

The mathematical concept of similarity, where forms maintain their proportional relationships while changing size, plays a crucial role in creating hierarchical pattern systems that work effectively at multiple scales simultaneously. This scale invariance allows single pattern systems to provide unified decorative schemes for entire architectural complexes while maintaining visual interest and appropriate detail at all viewing distances.

Harmonic proportions derived from musical relationships appear in some sophisticated Islamic geometric patterns, reflecting the medieval Islamic understanding of the mathematical relationships between visual and auditory harmony. These musical proportions create compositions that possess both visual and metaphysical resonance, connecting geometric design to broader Islamic concepts of cosmic harmony and divine order.

The systematic application of proportional relationships throughout complex geometric compositions requires sophisticated mathematical planning and execution. Master pattern designers developed computational methods and construction techniques that enabled them to maintain harmonic relationships while achieving high levels of visual complexity and decorative sophistication.

Dynamic proportional systems, where ratios change systematically according to mathematical rules, create patterns with built-in rhythmic variation that prevents visual monotony while maintaining overall coherence. These dynamic systems demonstrate advanced mathematical understanding and sophisticated aesthetic judgment in their application to decorative design.

Tessellation Principles and Grid Systems

The mathematical principles of tessellation that govern Islamic geometric patterns represent one of the most sophisticated achievements in decorative mathematics, demonstrating how abstract mathematical concepts can be transformed into visually compelling compositions that serve both aesthetic and spiritual purposes within Islamic cultural contexts.

Regular tessellations using only one type of regular polygon are limited to three possibilities: triangular, square, and hexagonal grids. Islamic designers explored all three possibilities extensively but achieved their greatest innovations through semi-regular and irregular tessellations that combine different polygonal elements according to precise mathematical rules.

Semi-regular tessellations, which use two or more types of regular polygons arranged so that each vertex has the same polygonal configuration, provide the mathematical foundation for many of the most sophisticated Islamic geometric patterns. These semi-regular arrangements create more complex visual effects than regular tessellations while maintaining the mathematical rigor necessary for perfect infinite repetition.

The mathematical constraints imposed by tessellation requirements actually stimulate creativity by providing clear parameters within which designers must work. The need to achieve perfect fit between adjacent elements while maintaining visual interest and symbolic content pushed Islamic designers to develop increasingly sophisticated solutions that represent pinnacles of geometric achievement.

Dual tessellations, created by connecting the centers of adjacent polygons in an existing tessellation, provide systematic methods for generating new pattern families from existing ones. This mathematical concept of duality creates relationships between different pattern types while providing designers with systematic methods for developing variations and related compositions.

The Voronoi tessellation principle, though not explicitly understood by medieval designers, governs many Islamic geometric patterns where space is divided according to proximity relationships around regularly distributed points. These Voronoi-based patterns create organic-looking compositions that maintain rigorous mathematical structure while achieving naturalistic visual effects.

Penrose-type quasiperiodic tessellations, which tile the plane without repetition while maintaining local regularity, appear in some sophisticated Islamic patterns that were created centuries before their mathematical properties were formally understood. These quasiperiodic patterns demonstrate the remarkable mathematical intuition of Islamic pattern designers and their willingness to explore geometric possibilities beyond conventional periodic systems.

Grid transformation techniques, where basic tessellation patterns are modified through systematic distortion or projection, create pattern families that share common mathematical foundations while displaying different visual characteristics. These transformation methods provide systematic approaches to pattern variation that maintain mathematical coherence while achieving diverse aesthetic effects.

The mathematical concept of fundamental domains, the smallest area that generates an entire pattern through systematic repetition, provides essential tools for understanding and constructing Islamic geometric patterns. The identification and manipulation of fundamental domains enables efficient pattern development and provides mathematical foundations for systematic variation and elaboration.

Color Theory and Mathematical Distribution

The sophisticated color systems that characterize authentic Moroccan geometric patterns reflect mathematical principles of distribution and alternation that enhance geometric structure while creating additional layers of visual complexity and symbolic meaning. These color systems demonstrate how mathematical concepts can be applied to non-geometric aspects of design to achieve unified compositions that work effectively on multiple levels simultaneously.

Mathematical color alternation systems, where colors change according to systematic rules based on geometric properties, create rhythmic variations that enhance pattern readability while maintaining overall visual unity. These alternation systems require careful mathematical planning to ensure that color changes reinforce rather than conflict with underlying geometric relationships.

Symmetry-based color distribution, where colors are assigned according to the symmetry operations that generate the pattern, creates systematic relationships between color and geometry that enhance both aspects of the design. This approach ensures that color changes emphasize important geometric relationships while maintaining the mathematical coherence of the overall composition.

The mathematical principle of duality applies to color systems as well as geometric structure, where patterns can be transformed by systematically exchanging colors according to mathematical rules. These color duality relationships create families of related patterns that share common geometric structure while displaying different color characteristics and visual effects.

Conclusion

Hierarchical color systems, where different levels of pattern complexity receive different color treatments, create compositions with enhanced visual depth and complexity while maintaining clarity and readability. These hierarchical approaches require sophisticated understanding of both geometric structure and color relationships to achieve effective results.

Mathematical color progression systems, where colors change systematically according to geometric or numerical sequences, create dynamic visual effects that enhance pattern movement and vitality. These progression systems demonstrate how mathematical concepts can be applied to create temporal as well as spatial effects in static decorative compositions.

The mathematical optimization of color contrast ensures that pattern elements remain clearly distinguishable while maintaining overall visual harmony. This optimization requires understanding of both color theory and geometric structure to achieve compositions that work effectively under various lighting conditions and viewing distances.

Regional color preferences within Moroccan decorative traditions reflect both aesthetic choices and mathematical constraints imposed by available materials and production techniques. The integration of these practical considerations with mathematical color principles demonstrates the sophisticated problem-solving abilities of traditional pattern designers.

The extraordinary craft of zellige mosaic tilework emerged in the 10th century within the cultural crucible of Fez, evolving from Byzantine and Roman mosaic traditions while developing distinctive characteristics that reflected Islamic aesthetic principles and spiritual values. This ancient art form represents one of humanity's most sophisticated approaches to ceramic decoration, requiring exceptional skill, mathematical precision, and deep cultural understanding to achieve authentic results.

The foundational techniques of zellige production developed during the Almoravid period when master craftspeople began experimenting with local clay deposits found near Fez. These unique clay sources, formed over geological time through specific mineral combinations and environmental conditions, proved ideal for creating the fine-grained, highly plastic ceramic body necessary for precise mosaic work. The discovery and exploitation of these clay deposits established Fez as the undisputed center of zellige production, a position the city maintains to this day.

The emergence of geometric patterns in Islamic decoration resulted partly from religious prohibitions against figurative representation, which channeled artistic creativity toward abstract and mathematical forms that could convey spiritual meaning without depicting recognizable objects or living beings. This theological constraint became a liberating force that pushed artisans to explore increasingly sophisticated geometric possibilities, ultimately leading to the development of pattern systems of unprecedented complexity and beauty.