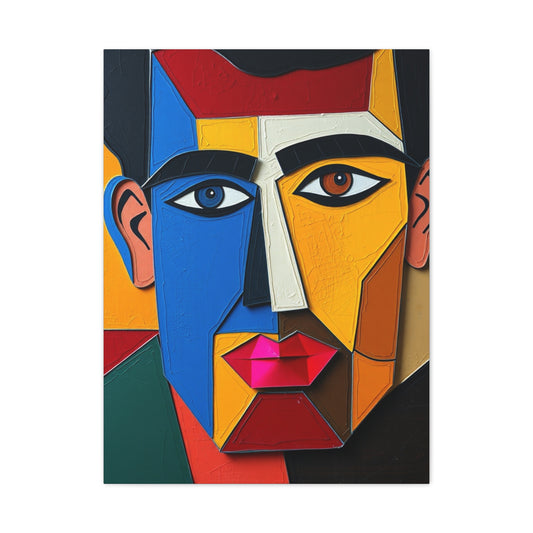

Collection: Cubism Wall Art

An Introduction To Cubism Wall Art And The Cubist Art Movement

"Cubism is like standing at a certain point on a mountain and looking around. If you go higher, things will look different; if you go lower, again they will look different. It is a point of view." - Jacques Lipchitz

Cubism emerged as a revolutionary avant-garde art movement during the early twentieth century, fundamentally transforming how artists perceived and represented reality. This groundbreaking aesthetic philosophy challenged conventional artistic traditions, offering a radical departure from naturalistic representation toward a more conceptual approach to visual expression.

Origins and Revolutionary Beginnings

The birth of Cubism represented a seismic shift in artistic consciousness, emerging from the ferment of early twentieth-century modernism. This revolutionary movement arose as artists grappled with rapidly changing social, industrial, and intellectual landscapes. The traditional Renaissance perspective, which had dominated Western art for centuries, suddenly seemed inadequate for expressing the complexity of modern experience.

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the movement's primary architects, initiated this artistic revolution around 1907. Their collaboration began organically, driven by shared dissatisfaction with conventional representational methods. Both artists recognized that traditional painting techniques failed to capture the multifaceted nature of human perception and experience.

The movement's genesis can be traced to specific catalytic moments. Picasso's encounter with African masks at the Trocadéro Museum in Paris profoundly influenced his artistic vision. These artifacts demonstrated alternative approaches to representing the human form, emphasizing geometric simplification and symbolic rather than naturalistic representation. Similarly, Paul Cézanne's later works, with their emphasis on geometric forms and multiple perspectives, provided crucial inspiration for the developing cubist aesthetic.

The intellectual climate of early twentieth-century Paris fostered this artistic experimentation. Scientific discoveries, particularly Einstein's theory of relativity, challenged traditional notions of space and time. Simultaneously, philosophical movements questioned absolute truths and emphasized subjective experience. This intellectual ferment created fertile ground for artistic innovation, encouraging artists to explore new ways of representing reality.

The term "Cubism" itself emerged somewhat accidentally. Art critic Louis Vauxcelles, describing Georges Braque's 1908 painting "Houses at L'Estaque," remarked on the artist's reduction of forms to geometric cubes. This seemingly dismissive comment became the movement's defining moniker, though the artists themselves initially resisted the label.

Early cubist works demonstrated a radical departure from traditional artistic conventions. Artists abandoned linear perspective, chiaroscuro, and naturalistic color in favor of geometric fragmentation and multiple viewpoints. This approach reflected a philosophical shift toward representing objects as conceptualized rather than merely observed, emphasizing the mind's role in constructing visual experience.

The movement's revolutionary nature extended beyond mere stylistic innovation. Cubism challenged fundamental assumptions about art's relationship to reality, questioning whether painting should mirror the visible world or reveal deeper truths about existence. This philosophical dimension elevated Cubism beyond a simple artistic style to a comprehensive worldview that influenced subsequent artistic developments.

Philosophical Underpinnings and Theoretical Framework

Cubism's philosophical foundations rested on fundamental questions about perception, reality, and representation. The movement challenged traditional Western notions of visual truth, proposing instead that artistic representation should reflect the complexity of human consciousness rather than simple optical experience.

The cubist approach to representation drew heavily from phenomenological philosophy, which emphasized subjective experience over objective reality. Artists recognized that human perception involves memory, emotion, and conceptual knowledge alongside immediate sensory input. A cubist painting therefore attempted to synthesize these various modes of understanding into a single visual statement.

This philosophical approach manifested in the cubist treatment of space and time. Traditional painting captured a single moment from a fixed viewpoint, but cubist works incorporated multiple perspectives and temporal dimensions. A cubist portrait might show a face simultaneously from front and profile views, suggesting the artist's accumulated knowledge of the subject rather than a momentary glimpse.

The movement's theoretical framework also incorporated ideas from contemporary psychology and cognitive science. Early twentieth-century research into perception revealed that human vision involves active interpretation rather than passive recording. The eye constantly moves, focuses, and refocuses, building up a composite mental image from numerous individual observations. Cubist painting attempted to represent this perceptual process directly.

Cubist theory emphasized the conceptual over the perceptual. Artists argued that painting should represent what we know about objects rather than merely what we see. A cubist still life might show a bottle simultaneously from above and in profile, revealing its complete form rather than a single viewpoint. This approach reflected the belief that true understanding transcends momentary perception.

The movement's philosophical implications extended to questions of artistic truth and authenticity. Cubists argued that traditional realistic painting was actually highly artificial, imposing arbitrary conventions like single-point perspective that distorted natural perception. Their fragmented, multi-perspectival approach claimed greater fidelity to actual human experience.

Cubist theory also addressed the relationship between form and content. Traditional art often subordinated formal elements to narrative or symbolic content, but cubists emphasized form itself as meaningful. The geometric structure of a cubist painting carried significance equal to its representational content, reflecting the movement's materialist approach to artistic creation.

Cultural Context and Societal Influences

The emergence of Cubism cannot be understood apart from the broader cultural transformations occurring in early twentieth-century Europe. This period witnessed unprecedented social, technological, and intellectual changes that profoundly influenced artistic sensibilities and created demand for new forms of cultural expression.

The rapid industrialization of European society fundamentally altered human experience of space, time, and reality. Urban environments replaced rural landscapes as primary living spaces for increasing numbers of people. The geometric regularity of industrial architecture, the mechanical rhythms of factory production, and the fragmented experience of modern city life all found reflection in cubist artistic strategies.

Technological innovations, particularly in transportation and communication, revolutionized human perception of distance and simultaneity. Railway travel enabled rapid movement across geographical spaces, while telegraph and telephone systems facilitated instantaneous communication across vast distances. These experiences of compressed space and time influenced cubist experiments with multiple perspectives and temporal synthesis.

The period's intellectual ferment provided crucial context for cubist innovations. Scientific discoveries challenged traditional notions of absolute space and time, while philosophical movements questioned established truths and emphasized subjective experience. Psychoanalytic theories revealed the complexity of human consciousness, suggesting that surface appearances might conceal deeper realities.

Colonial expansion brought European artists into contact with non-Western artistic traditions. African masks, Oceanic sculptures, and other "primitive" artworks demonstrated alternative approaches to representation that emphasized symbolic and spiritual dimensions over naturalistic accuracy. These encounters profoundly influenced cubist artists, who incorporated non-Western aesthetic principles into their revolutionary visual language.

The emergence of mass media and mechanical reproduction fundamentally altered relationships between original artworks and their reproductions. Photography, in particular, challenged painting's traditional role as primary means of visual documentation. This technological pressure encouraged artists to explore painting's unique capabilities, leading to cubist emphasis on conceptual representation over mere optical recording.

World War I profoundly impacted cubist development, though the movement had emerged several years earlier. The war's mechanized violence and systematic destruction seemed to validate cubist insights about modern reality's fragmented, unstable character. Many cubist artists served in the military or worked as war artists, experiences that influenced their subsequent artistic development.

Aesthetic Principles and Visual Language

Cubism developed a distinctive visual language based on fundamental aesthetic principles that distinguished it from all previous artistic movements. These principles governed how cubist artists approached composition, color, form, and spatial organization, creating a coherent artistic methodology despite individual variations among practitioners.

The principle of multiple perspective constituted Cubism's most recognizable characteristic. Rather than depicting objects from a single fixed viewpoint, cubist artists showed subjects from various angles simultaneously. This approach reflected the belief that comprehensive understanding required synthesizing multiple observations rather than accepting a single momentary glimpse.

Geometric fragmentation provided another crucial cubist principle. Artists broke down observed forms into geometric components—cubes, cylinders, spheres, and planes—then reassembled these elements according to aesthetic rather than naturalistic logic. This fragmentation process revealed underlying structural relationships while emphasizing the artwork's constructed character.

The treatment of pictorial space represented a radical departure from Renaissance traditions. Instead of creating illusory depth through linear perspective, cubist artists flattened spatial relationships, bringing background elements forward while pushing foreground objects back. This spatial ambiguity emphasized the painting surface itself while challenging viewers' perceptual expectations.

Cubist color theory departed significantly from traditional approaches. Rather than using color to model form or create atmospheric effects, cubist artists employed limited palettes to unify fragmented compositions. Early cubist works often featured monochromatic schemes of browns, grays, and ochres that emphasized structural relationships over surface appearances.

The principle of conceptual rather than perceptual representation guided cubist approaches to subject matter. Artists depicted objects based on accumulated knowledge rather than immediate observation. A cubist painting of a violin might show its sound holes, strings, and internal structure simultaneously, presenting a complete conceptual portrait rather than a single visual impression.

Cubist compositions emphasized dynamic equilibrium over static balance. Fragmented forms created visual tensions that activated the entire picture surface, engaging viewers in active interpretive processes. This compositional strategy reflected modern life's energetic, unstable character while demanding sustained attention from observers.

The integration of text and image represented another innovative cubist principle. Artists incorporated letters, numbers, and words directly into their compositions, blurring boundaries between visual and linguistic communication. This integration reflected the movement's interest in signs and symbols as fundamental elements of modern experience.

Precursors and Intellectual Influences

The revolutionary character of Cubism should not obscure its connections to earlier artistic and intellectual developments. Multiple precursors and influences contributed to the movement's emergence, creating a complex genealogy that reveals cubist innovations as both radical departures and logical developments from existing traditions.

Paul Cézanne's influence on cubist development cannot be overstated. His late works demonstrated approaches to form and space that anticipated cubist innovations. Cézanne's emphasis on geometric reduction, his treatment of natural forms as cylinders, cones, and spheres, and his experiments with multiple perspectives provided direct inspiration for Picasso and Braque. His famous advice to "treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone" became a fundamental cubist principle.

The discovery of non-Western art, particularly African masks and sculptures, profoundly influenced cubist aesthetic development. These artifacts demonstrated that artistic representation need not mirror natural appearances but could emphasize symbolic, spiritual, or conceptual dimensions. The geometric simplification and expressive distortion characteristic of African art provided models for cubist experiments with form and meaning.

Henri Rousseau's naive painting style, though superficially different from cubist sophistication, offered important lessons about artistic authenticity and directness. Rousseau's disregard for academic conventions and his emphasis on imagination over observation influenced cubist artists' willingness to abandon traditional techniques in pursuit of more direct expression.

Medieval art provided another significant influence, particularly manuscript illuminations and Gothic sculpture. These works demonstrated approaches to space and form that differed radically from Renaissance naturalism. Medieval artists' willingness to distort natural proportions for expressive purposes and their integration of text and image offered precedents for cubist innovations.

The influence of contemporary literature and philosophy cannot be ignored. Writers like Guillaume Apollinaire and Gertrude Stein experimented with fragmented, non-linear narrative techniques that paralleled cubist visual strategies. Philosophical movements, particularly phenomenology and pragmatism, provided theoretical frameworks that supported cubist approaches to representation and meaning.

Scientific developments, especially in mathematics and physics, influenced cubist thinking about space, time, and perception. Non-Euclidean geometry suggested that traditional spatial concepts might be arbitrary constructions rather than absolute truths. Einstein's relativity theory challenged assumptions about simultaneous events and fixed perspectives, providing scientific validation for cubist artistic experiments.

The emergence of photography as a dominant visual medium created both challenges and opportunities for painting. Photography's ability to record visual appearances with unprecedented accuracy forced painters to reconsider their medium's unique capabilities. This pressure encouraged cubist exploration of painting's conceptual rather than merely representational possibilities.

Early Masterworks and Breakthrough Paintings

The development of Cubism can be traced through specific masterworks that demonstrate the movement's evolution from tentative experiments to mature artistic statements. These breakthrough paintings reveal how individual artists developed cubist principles while contributing to the movement's collective advancement.

Pablo Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" (1907) stands as Cubism's foundational masterpiece. This revolutionary painting abandoned traditional beauty standards and spatial conventions, presenting five female figures through radical geometric simplification. The work's African-influenced masks and fragmented forms shocked contemporary viewers while establishing key cubist principles. The painting's treatment of space, with its flattened picture plane and multiple perspectives, provided a template for subsequent cubist developments.

Georges Braque's "Houses at L'Estaque" (1908) series demonstrated the systematic application of cubist principles to landscape painting. These works reduced architectural forms to geometric essentials while exploring relationships between positive and negative space. Braque's subtle color harmonies and careful compositional balance showed how cubist fragmentation could achieve new forms of aesthetic unity.

Picasso's "Portrait of Ambroise Vollard" (1910) exemplified Analytic Cubism's mature phase. This complex composition fragmented the subject into countless geometric facets while maintaining recognizable portraiture elements. The painting's monochromatic palette and intricate surface patterns demonstrated how cubist analysis could reveal character and personality through formal means rather than conventional representation.

Braque's "Violin and Candlestick" (1910) explored cubist approaches to still life composition. The painting's treatment of musical instruments, with their complex curves and hollow spaces, challenged artists to develop new representational strategies. Braque's solution involved showing multiple aspects of objects simultaneously while creating rhythmic relationships between fragmented forms.

Juan Gris's "The Breakfast" (1914) represented Synthetic Cubism's more decorative and colorful phase. This painting integrated collage elements with painted forms, creating complex relationships between reality and representation. Gris's precise geometric organization and sophisticated color relationships demonstrated how cubist principles could achieve classical balance and harmony.

Fernand Léger's "The City" (1919) applied cubist principles to urban subject matter, celebrating modern industrial civilization through geometric abstraction. The painting's bold colors and mechanical forms reflected cubist engagement with contemporary technological culture while maintaining the movement's commitment to formal innovation.

Marcel Duchamp's "Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2" (1912) extended cubist principles toward kinetic representation. This controversial painting attempted to show motion through temporal synthesis, presenting multiple phases of movement within a single composition. The work's reception at the 1913 Armory Show in New York demonstrated Cubism's international impact and controversial status.

Global Spread and International Variations

Cubism's influence extended far beyond its Parisian origins, inspiring artists throughout Europe and the Americas to develop local variations of cubist principles. This international spread demonstrated the movement's universal relevance while revealing how different cultural contexts shaped artistic interpretation of cubist ideas.

The movement's expansion to other European centers occurred rapidly. In Germany, artists like Franz Marc and August Macke incorporated cubist fragmentation into Expressionist color theories, creating dynamic syntheses of French and German artistic traditions. The Blue Rider group's exhibitions featured cubist works alongside German avant-garde paintings, facilitating cross-cultural artistic dialogue.

Italian Futurism demonstrated another significant cubist influence. Artists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla adopted cubist fragmentation techniques while emphasizing dynamic movement and technological themes. Futurist paintings combined cubist formal innovations with distinctly Italian concerns about modernity, speed, and cultural transformation.

Russian artists developed particularly sophisticated responses to cubist innovations. Kazimir Malevich's Suprematism and Vladimir Tatlin's Constructivism both drew heavily from cubist principles while pursuing distinctly Russian artistic and political goals. These movements translated cubist formal innovations into revolutionary social programs, demonstrating the style's potential political implications.

The movement's arrival in the United States through the 1913 Armory Show created significant controversy and lasting influence. American artists like Stuart Davis and Charles Demuth developed distinctly American versions of cubist aesthetics, incorporating local subject matter and cultural references while maintaining European formal innovations.

Latin American artists found particular resonance with cubist principles, which seemed to validate indigenous artistic traditions that emphasized conceptual over naturalistic representation. Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera incorporated cubist techniques into politically engaged public artworks, while Brazilian artists developed tropical variations of European cubist themes.

The movement's spread to Asia occurred more gradually but proved equally significant. Japanese artists like Yorozu Tetsugorō developed sophisticated syntheses of cubist principles with traditional Japanese aesthetic concepts. Chinese artists in the 1920s and 1930s used cubist techniques to address questions of cultural identity and modernization.

Deconstructing Reality Through Geometric Analysis

Analytical Cubism, spanning approximately from 1909 to 1912, represented the movement's most radical phase in terms of dismantling traditional representational conventions. This period witnessed artists systematically analyzing and decomposing observed reality into geometric components, creating a new visual language that challenged fundamental assumptions about artistic representation.

The analytical process began with careful observation of subjects, but quickly moved beyond mere recording toward conceptual investigation. Artists examined objects from multiple angles, studying their structural relationships and essential characteristics. This investigation process resembled scientific methodology, with artists functioning as visual researchers exploring the nature of form and space.

The geometric vocabulary developed during this period emphasized basic shapes—cubes, cylinders, cones, and planes—that could be manipulated and recombined according to aesthetic logic. Artists discovered that complex natural forms could be reduced to geometric essentials without losing essential character or meaning. This reduction process revealed underlying structural relationships while emphasizing the constructed nature of artistic representation.

Spatial relationships underwent radical transformation during the Analytical phase. Traditional Renaissance perspective, with its fixed viewpoint and systematic recession, gave way to multiple simultaneous perspectives. Artists might show a face from front and profile views within the same composition, creating temporal synthesis that suggested accumulated observation rather than momentary glimpse.

The treatment of light and shadow departed significantly from traditional chiaroscuro techniques. Instead of using light to model three-dimensional forms, analytical cubists employed geometric faceting to suggest volume and depth. Light became fragmented and distributed across geometric planes, creating complex patterns that activated entire compositions rather than simply illuminating specific forms.

Color relationships during this period emphasized structural unity over naturalistic accuracy. Most analytical cubist works employed restricted palettes of browns, grays, and ochres that unified fragmented compositions while directing attention toward formal relationships rather than surface attractions. This monochromatic approach reflected the movement's emphasis on essential rather than accidental characteristics.

The relationship between figure and ground underwent fundamental reconsideration. Traditional painting clearly distinguished between subject and background, but analytical cubists integrated these elements into unified compositional structures. Background elements might project forward while foreground objects receded, creating spatial ambiguities that challenged conventional perceptual expectations.

Master Practitioners and Their Distinctive Approaches

While Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque developed Analytical Cubism collaboratively, each artist maintained distinctive approaches that revealed different aspects of the style's potential. Their parallel investigations created a rich dialogue that advanced the movement while demonstrating individual artistic personalities within shared aesthetic frameworks.

Picasso's analytical works emphasized dramatic structural relationships and bold geometric contrasts. His approach to fragmentation tended toward angular, crystalline forms that created dynamic tensions across compositional surfaces. Picasso's analytical portraits, such as those of Ambroise Vollard and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, demonstrated how geometric analysis could reveal personality and character through formal means rather than conventional portraiture techniques.

The Spanish artist's analytical still lifes explored relationships between organic and geometric forms. His treatment of musical instruments, bottles, and books revealed how everyday objects could be transformed into complex geometric compositions while retaining recognizable identity. Picasso's analytical process often emphasized contrast and juxtaposition, creating visual dramas from mundane subject matter.

Braque's analytical approach emphasized subtle harmonies and measured compositional relationships. His geometric fragments tended toward curved, faceted forms that created gentler transitions between shapes. Braque's analytical landscapes, particularly his views of L'Estaque, demonstrated how cubist principles could be applied to outdoor subjects while maintaining intimate scale and careful observation.

The French artist's analytical still lifes revealed his background as a house painter through sophisticated understanding of surface textures and material relationships. Braque's treatment of musical instruments emphasized their acoustic properties, creating visual equivalents for sound through geometric analysis. His compositions often achieved classical balance despite radical fragmentation.

Juan Gris emerged as a significant analytical practitioner, bringing mathematical precision to cubist investigations. His analytical works demonstrated systematic approaches to geometric organization, often employing golden section proportions and careful modular relationships. Gris's analytical portraits and still lifes revealed how cubist principles could achieve both conceptual clarity and visual beauty.

Fernand Léger developed distinctive mechanical approaches to analytical fragmentation. His analytical works emphasized cylindrical and tubular forms that suggested industrial machinery and modern technology. Léger's analytical figure paintings transformed human bodies into mechanical assemblages, reflecting contemporary fascination with industrial civilization.

Marcel Duchamp's analytical experiments pushed cubist principles toward temporal synthesis and kinetic representation. His analytical paintings attempted to show movement and change through geometric fragmentation, exploring time as well as space within cubist frameworks. These investigations would later lead Duchamp beyond painting toward conceptual art practices.

Technical Innovations and Artistic Methods

The development of Analytical Cubism required significant technical innovations as artists adapted traditional painting methods to serve radical new aesthetic purposes. These technical developments represented genuine discoveries that expanded painting's expressive possibilities while creating new challenges for artistic execution.

Canvas preparation and ground application required modification to support analytical compositional strategies. Traditional grounds emphasized smooth, uniform surfaces that facilitated naturalistic rendering, but analytical cubists often preferred slightly textured surfaces that enhanced geometric fragmentation effects. Some artists experimented with colored grounds that influenced overall color harmonies while providing structural foundation for complex compositions.

Brushwork techniques evolved to emphasize geometric construction over naturalistic modeling. Artists developed systematic approaches to mark-making that reinforced compositional structures rather than simply describing surface appearances. Brushstrokes became architectural elements that built up geometric planes and created visual rhythms across compositional surfaces.

The development of passage techniques represented a crucial analytical innovation. This method involved leaving edges incomplete or ambiguous, allowing forms to merge and separate in continuous visual flow. Passage techniques enabled artists to maintain compositional unity despite radical fragmentation, creating connections between geometric fragments that suggested underlying structural relationships.

Color mixing and application methods required adaptation to serve analytical purposes. Artists learned to use color structurally rather than descriptively, employing subtle variations to distinguish geometric planes while maintaining overall compositional harmony. The development of modulated color systems enabled artists to create volume and depth through color relationships rather than traditional chiaroscuro techniques.

Drawing methods underwent fundamental transformation as artists learned to construct rather than copy observed forms. Analytical drawing emphasized structural analysis over surface description, requiring artists to understand objects conceptually before attempting representation. This approach demanded sophisticated understanding of geometric relationships and spatial organization.

Compositional planning became increasingly important as analytical complexity grew. Artists developed systematic approaches to organizing fragmented elements into coherent wholes, often employing preliminary studies and careful geometric analysis. Some artists used mathematical proportions and modular systems to ensure compositional unity despite surface complexity.

The relationship between observation and invention required careful balance as artists learned to analyze without losing essential character. Successful analytical paintings maintained recognizable connection to observed subjects while transforming them through geometric investigation. This balance demanded both rigorous analysis and creative synthesis.

Subject Matter and Thematic Concerns

Analytical Cubism developed characteristic approaches to subject matter that reflected the movement's conceptual concerns while revealing practical limitations of analytical methods. The choice and treatment of subjects demonstrated how analytical techniques could reveal essential characteristics while transforming traditional artistic categories.

Portrait painting underwent radical transformation as artists learned to represent personality and character through geometric analysis rather than conventional likeness. Analytical portraits emphasized structural relationships and formal characteristics that revealed subjects' essential nature rather than momentary appearance. These works challenged traditional notions of portraiture while creating new possibilities for psychological representation.

The treatment of portrait subjects often emphasized professional or intellectual characteristics rather than physical beauty. Artists like Picasso and Braque portrayed dealers, writers, and musicians whose intellectual pursuits seemed compatible with analytical investigation. These subjects' complex personalities provided rich material for geometric exploration while suggesting connections between artistic and intellectual analysis.

Still life painting proved particularly suitable for analytical treatment because objects could be studied extensively and from multiple viewpoints. Musical instruments, bottles, newspapers, and books became favorite subjects due to their geometric complexity and cultural significance. These objects' familiar forms provided recognizable reference points within radical compositional transformations.

The symbolic dimensions of still life subjects gained increased importance as analytical fragmentation reduced descriptive clarity. Musical instruments suggested harmony and rhythm, newspapers implied contemporary events, and bottles or glasses evoked social rituals. These symbolic associations enriched analytical compositions while providing interpretive frameworks for viewers encountering radical formal innovations.

Landscape painting presented significant challenges for analytical treatment due to its scale and atmospheric complexity. Most analytical landscapes focused on architectural subjects like buildings and trees that could be reduced to geometric components. Urban and suburban views proved more suitable than wild natural scenes for analytical investigation.

The treatment of architectural subjects emphasized structural relationships and geometric organization over atmospheric effects. Buildings provided ready-made geometric subjects that could be analyzed and reconstructed according to aesthetic logic. These subjects' angular forms and clear spatial relationships facilitated analytical experimentation while maintaining recognizable subject matter.

Figure painting during the analytical period emphasized conceptual rather than sensual representation. Human bodies were subjected to geometric analysis that revealed structural relationships while avoiding traditional emphasis on physical beauty or erotic appeal. This approach reflected the movement's intellectual rather than sensual orientation.

Spatial Innovations and Perspectival Experiments

Analytical Cubism's most revolutionary contributions concerned spatial representation and perspectival organization. Artists developed entirely new approaches to depicting three-dimensional relationships on two-dimensional surfaces, creating spatial systems that challenged Renaissance perspective while opening new possibilities for pictorial space.

The abandonment of single-point perspective represented Analytical Cubism's most dramatic spatial innovation. Instead of organizing compositions around fixed vanishing points, artists employed multiple simultaneous perspectives that suggested movement through space over time. This approach reflected actual human perceptual experience more accurately than traditional perspective systems.

The development of simultaneous multiple viewpoints enabled artists to show objects from various angles within single compositions. A cubist portrait might combine frontal and profile views, revealing facial structure more completely than traditional single-viewpoint representations. This synthesis of perspectives suggested analytical investigation rather than momentary observation.

Spatial recession underwent fundamental reconsideration as artists learned to organize depth relationships according to aesthetic rather than naturalistic logic. Background elements might project forward while foreground objects receded, creating spatial paradoxes that activated entire compositions. These spatial ambiguities demanded active viewer participation in constructing coherent interpretations.

The treatment of interior and exterior relationships challenged traditional spatial boundaries. Analytical compositions often merged indoor and outdoor spaces, combining architectural elements with landscape features in impossible but visually coherent arrangements. These spatial syntheses reflected modern urban experience while demonstrating painting's freedom from naturalistic constraints.

Scale relationships became increasingly arbitrary as artists manipulated object sizes according to compositional needs rather than naturalistic proportions. Small objects might dominate large ones, creating hierarchies based on artistic significance rather than physical reality. These scale manipulations emphasized painting's constructed character while directing attention toward essential rather than accidental characteristics.

The integration of temporal dimensions into spatial compositions represented another crucial innovation. Analytical paintings often suggested duration and change through geometric synthesis, showing objects in multiple states simultaneously. This temporal integration reflected contemporary interest in relativity and change while expanding painting's representational capabilities.

Atmospheric effects underwent geometric translation as artists learned to represent air, light, and space through fragmented planes rather than traditional modeling techniques. Atmosphere became architectonic, composed of geometric elements that could be manipulated and organized like solid forms. This geometric atmosphere maintained spatial suggestion while emphasizing surface pattern and design.

Color Theory and Chromatic Restraint

The color practices of Analytical Cubism represented a deliberate rejection of traditional coloristic approaches in favor of structural and unifying strategies. This chromatic restraint reflected the movement's emphasis on form over surface attraction while creating new possibilities for color's structural role in pictorial composition.

The adoption of monochromatic or near-monochromatic palettes characterized most analytical works. Artists typically employed ranges of browns, grays, and ochres that unified fragmented compositions while eliminating color as a source of visual distraction. This restraint directed attention toward formal relationships and geometric organization rather than chromatic beauty.

The development of modulated color systems enabled subtle distinctions between geometric planes without disrupting overall compositional unity. Artists learned to use slight color variations to suggest volume and depth while maintaining surface coherence. These modulated systems required sophisticated understanding of color relationships and careful execution.

Local color, meaning the natural color of objects, became largely irrelevant as artists pursued structural rather than descriptive color functions. A brown violin might appear in gray tones, while a white newspaper could be rendered in ochre. This liberation from descriptive accuracy enabled color to serve purely aesthetic purposes.

The relationship between warm and cool colors provided structural organization within restricted palettes. Artists often used warm browns and ochres for foreground elements while employing cooler grays for background areas. These temperature relationships created spatial depth despite overall chromatic restraint.

Color values, meaning relative lightness and darkness, gained increased importance as pure color intensity diminished. Artists developed sophisticated understanding of value relationships, using careful gradations to model forms and create spatial depth. This emphasis on value over hue reflected analytical emphasis on structure over surface.

The integration of color with linear elements created complex surface relationships that unified fragmented compositions. Colored geometric planes interacted with drawn lines to create rhythmic patterns across compositional surfaces. This integration demonstrated color's architectural potential within cubist frameworks.

Texture and surface quality became increasingly important as color intensity decreased. Artists explored various paint application methods to create surface variations that enriched restricted color schemes. These textural investigations would later influence Synthetic Cubism's collage experiments.

Emergence of Constructive Principles

Synthetic Cubism, flourishing from approximately 1912 to 1920, marked a fundamental shift from the analytical deconstruction of forms toward synthetic construction of new visual realities. This phase represented a mature understanding of cubist principles, where artists moved beyond breaking down observed reality to building up entirely new pictorial structures from geometric and representational elements.

The transition from analytical to synthetic approaches reflected growing confidence in cubist methodology and desire for more direct expressive possibilities. While analytical cubism required extensive observation and systematic deconstruction, synthetic cubism enabled artists to construct compositions from imagination, memory, and aesthetic preference. This shift represented liberation from naturalistic constraints toward pure artistic invention.

The constructive principles of synthetic cubism emphasized building compositions from discrete elements rather than fragmenting unified wholes. Artists learned to combine geometric shapes, representational fragments, and various materials into coherent artistic statements. This additive process resembled architectural or musical composition, where individual elements combined to create larger structures.

Color relationships became more complex and expressive during the synthetic phase as artists abandoned analytical monochrome for richer chromatic possibilities. Synthetic compositions often featured bold color contrasts and decorative patterns that emphasized aesthetic pleasure alongside conceptual investigation. This chromatic liberation reflected the movement's maturation and growing confidence.

The treatment of space continued evolving as artists developed new approaches to pictorial depth and surface organization. Synthetic compositions often employed layered construction methods that created spatial complexity through overlapping forms rather than perspectival recession. These layered approaches suggested collage methodology even in purely painted works.

Subject matter expanded during the synthetic phase as constructive methods enabled artists to address broader thematic concerns. While analytical cubism focused on careful observation of limited subjects, synthetic cubism could incorporate diverse elements from contemporary culture, including commercial imagery, popular entertainment, and social commentary.

The relationship between representation and abstraction became more fluid as synthetic artists learned to move freely between recognizable imagery and pure geometric construction. This flexibility enabled rapid stylistic changes and experimental approaches that kept cubist art responsive to changing cultural conditions.

Collage and Papier Collé Techniques

The introduction of collage and papier collé techniques represented Synthetic Cubism's most revolutionary innovation, fundamentally expanding artistic materials and methods while challenging traditional boundaries between art and everyday life. These mixed-media approaches enabled entirely new relationships between artistic representation and material reality.

Georges Braque initiated the collage revolution around 1912 when he began incorporating pieces of wallpaper, newspaper, and other materials directly into his compositions. This breakthrough recognized that artistic representation need not rely exclusively on painted illusion but could include actual materials from the represented world. A piece of newspaper could represent itself while functioning as part of a larger artistic composition.

The development of papier collé, meaning pasted paper, provided systematic methods for incorporating various materials into cubist compositions. Artists learned to select papers based on color, texture, and printed content, using these materials as both formal elements and symbolic references. A fragment of Le Figaro newspaper might function as gray geometric shape while referencing contemporary events.

Collage techniques enabled unprecedented relationships between reality and representation. A piece of actual rope could represent rope within a still life while maintaining its material identity as rope. This dual existence challenged traditional distinctions between artistic illusion and physical reality, suggesting that art could incorporate rather than simply represent the external world.

The selection and preparation of collage materials required new artistic skills and aesthetic sensibilities. Artists learned to recognize visual potential in everyday materials, transforming commercial packaging, news media, and industrial products into artistic components. This transformation process demonstrated art's ability to find beauty and meaning in overlooked aspects of modern life.

Compositional strategies adapted to accommodate mixed media elements as artists learned to integrate pasted materials with painted forms. Successful collage compositions balanced material contrasts while maintaining overall unity, requiring sophisticated understanding of visual relationships between different media types.

The temporal dimensions of collage materials added historical layers to cubist compositions. Newspaper fragments carried specific dates and news references, while commercial packaging reflected particular historical moments. These temporal references enabled artistic commentary on contemporary events while creating historical documents of daily life.

Texture relationships became increasingly important as artists explored contrasts between smooth papers, rough materials, and painted surfaces. These textural variations enriched visual experience while emphasizing the constructed nature of artistic compositions. The physical reality of pasted materials contrasted with painted illusions, creating perceptual tensions that activated viewer attention.

Conclusion

Several artists emerged as masters of papier collé technique, each developing distinctive approaches that expanded the medium's expressive possibilities while revealing different aspects of synthetic cubist methodology. These practitioners transformed collage from experimental technique to mature artistic medium with unlimited creative potential.

Georges Braque's papier collé works demonstrated masterful integration of pasted materials with painted elements, creating compositions that achieved both material richness and classical harmony. His selection of papers emphasized subtle color relationships and elegant proportional systems that maintained cubist structural principles while exploiting collage's decorative possibilities.

Braque's approach to newspaper integration revealed particular sensitivity to textual content and typographic design. His compositions often incorporated news headlines and commercial advertisements that commented obliquely on depicted subjects while creating layers of cultural reference. These textual elements functioned simultaneously as formal components and semantic content.

The French artist's treatment of musical themes through collage techniques demonstrated how mixed media could enhance subject-specific associations. His papier collé still lifes of musical instruments incorporated sheet music fragments and concert programs that reinforced musical references while contributing to compositional structure.

Pablo Picasso's collage experiments revealed characteristically bold and experimental approaches to mixed media composition. His incorporation of diverse materials—from wallpaper and newsprint to sand and charcoal—demonstrated collage's potential for radical material contrasts and unexpected aesthetic combinations.

Picasso's approach to figural subjects through collage techniques created particularly innovative solutions to representational challenges. His collaged portraits and figure studies demonstrated how mixed media could suggest human presence through material associations rather than conventional drawing methods.

The Spanish artist's integration of found materials with invented forms revealed sophisticated understanding of relationships between reality and artistic construction. His compositions often played with perceptual expectations, using realistic materials to create impossible spatial relationships or fantastic combinations.